Month: June 2010

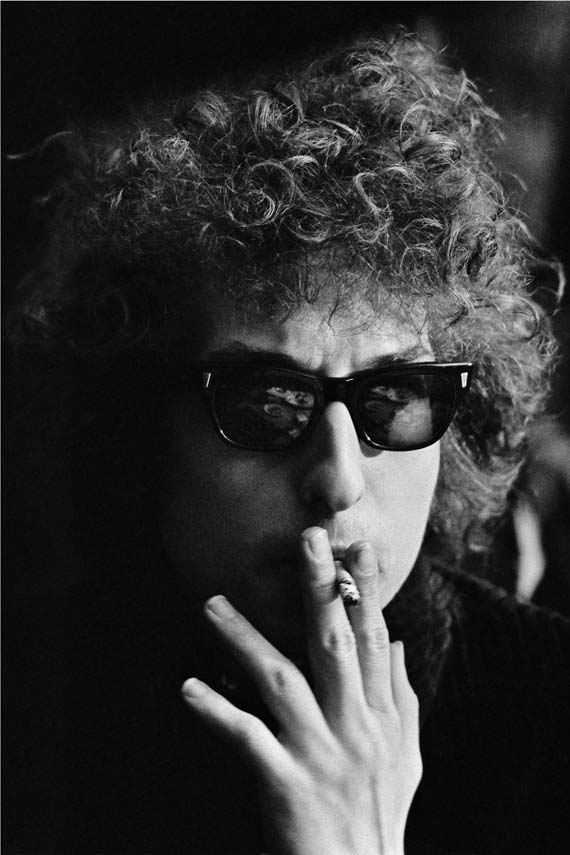

Bent Rej/Sixties Rock Legends Onstage Backstage

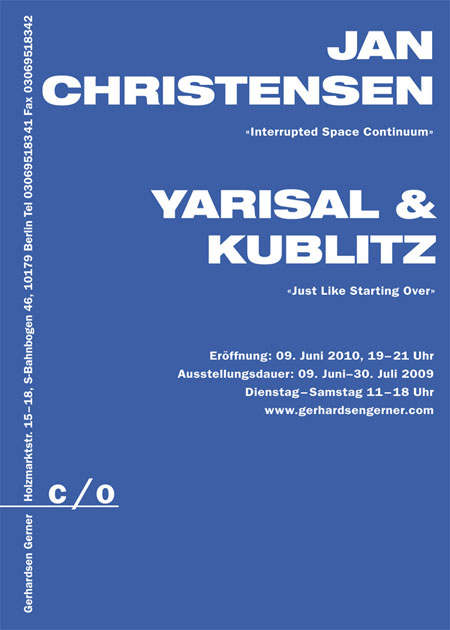

YARISAL & KUBLITZ

Alex Brown // Nobody Knows This is Somewhere

Summerbreak //

Other Sky //

Copenhagen Graffiti (Walls)

James White // Max Wigram Gallery

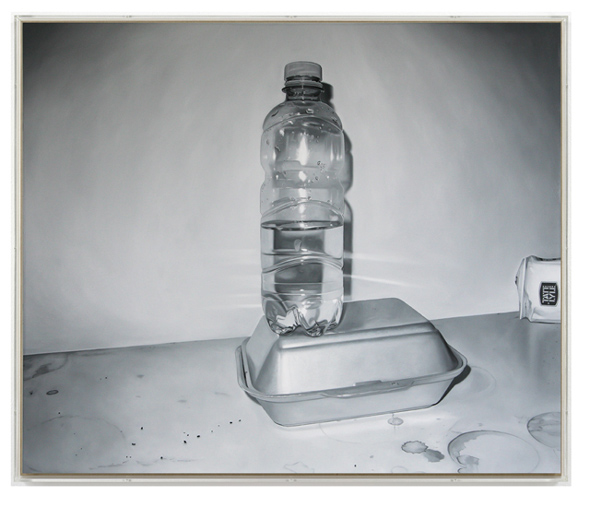

Max Wigram Gallery is proud to announce an exhibition of new paintings by James White.

The works continue White’s archiving of the minutiae of modern life. His black and white oil paintings on plywood panels are composed from the snapshots the artist takes of the objects that surround him.

Like the cinematic ‘cutaway shot’, White’s images are deliberately emptied of any dramatic content of their own; our focus momentarily rests on an intimate group of objects that silently resonate within a grander scheme. In refusing to acknowledge a wider visual world, White’s exacting gaze suggests an external narrative in much the same way that the simple image of a drinking glass might when scrutinized within the context of a crime scene photograph.

Rather than merely celebrating the inherent beauty of the banal, White’s paintings are iconic, subtle reflections on the quotidian. Despite the sense of intimacy within the work, the artist equally distances the viewer from the scenes he represents. This detachment is intensified by the characteristic absence of colour and the presentation of the paintings encapsulated in Perspex box-like frames.

The paintings in the show derive from photographs taken mainly in hotel rooms and the artist’s studio. Both locations exacerbate the sense of isolation and quiet respite from the day to day. 2.40 am (Berlin Hotel) and 2.45 am (Berlin Hotel) show personal objects scattered around a hotel room where the artist is spending a sleepless night. These personal belongings are the only reminders of the artist’s presence in the room, the sole evidence of the occupier within an otherwise totally impersonal space.

Hangers (home) and Hangers (away) show the inside of two wardrobes, one in the artist’s home, the other in a hotel. In each painting, a single empty coat hanger dominates, reinforcing a feeling of absence and dislocation.

Burgerbox shows the remains of lunch in the artist’s studio. Here, and in Milk and Stuff and The Radio, we are reminded of the solitary nature of life in the studio. Removed from any significant action, the featured objects are however witnesses to the artist’s activity. Rendered immaculately, with impeccable attention to detail, these simple still lives conjure up human presence through its very absence.

White (b. 1967, UK) lives and works in London. Solo shows include: c/o Atle Gerhardsen, Berlin (2009); Goss Michael Foundation, Dallas; Max Wigram Gallery (2007). Exhibitions in 2010 include: ‘Realism- The Adventure of Reality’, Kunsthalle der Hypo-Kulturstiftung, Munich (Germany); Dawnbreakers’, John Hansard Gallery, Southampton. Group exhibitions include: The Saatchi Gallery (New Blood, 2004); The New Art Gallery, Walsall (Blue, 2000); Fig-1 (Atoll, 2000) and Casey Kaplan Gallery, New York (solos in 1997 and 2000). In 2006, he was a prize winner in the prestigious John Moores Contemporary Painting Prize.

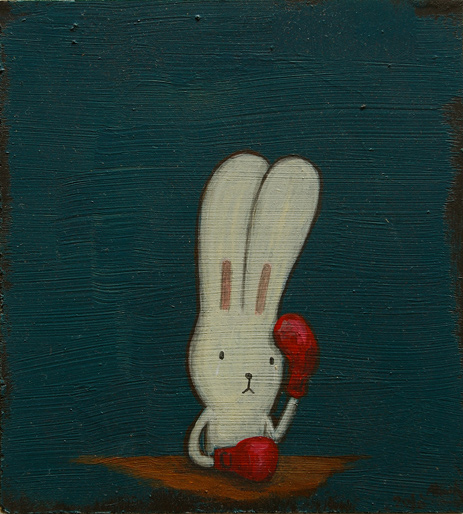

ATSUSHI KAGA // REST WITH US IN PEACE

Macbeth, the un-innocent, a metaphor of ordinary decency corrupted, is not in a happy place. Duncan done-for, the most famous of fictional murderers is riddled with appropriate, but somehow unexpected self-doubt and guilt that denies him nature’s cure-all remedy, the balm of sleep. Only the innocent, it would seem, the pure of heart, are afforded nature’s fundamental right, and innocence is done best in the unpremeditated behaviour of the animal kingdom. Enter Atshusi Kaga, stage left, whose art is almost entirely mediated through his alter ego, Usacchi (a loveable trickster rabbit) and the attendant cast of animal avatars who speak in metaphoric tongues to the daily struggle with our contemporary world.

The practice of Atsushi Kaga (born Japan 1978, lives and works in Dublin) is as philosophically and physcologically dense as it is intentionally deceptive. The fact that it manifests itself in the classical Japanese popularist cultural disciplines of Anime and Manga, with all their apparently attendant cuteness, masks the darker intentions of an artist intelligently working with the tools of incisive humour and social satire, conflating personal narratives and references to popular culture. In conversation at his IMMA studio, Atsushi Kaga draws attention towards two oddly diverse but equally significant influences on this much-anticipated second exhibition, Rest with us in peace, at mother’s tankstation. He cites the Myotonic Goat and Sunny Liston’s three encounters with Muhammad Ali in 1964-5. These may seem like odd reference points for Kaga, but for anyone who has become familiar with his practice over the past few years would have come to expect the unexpected, his imagination knows few bounds.

Firstly, the Myotonic goat… When startled, younger goats with the hereditary genetic disorder myotonia congenita will suddenly stiffen, blackout and fall over where they stand/stood at any impending sign of stress or threat. Older goats appear to ‘learn’ from experience (?), reflexively spreading their legs or leaning against something when a moment of terror besets them. Curiously, this phenomenological development denies them the very essence to escape from trauma, as they often continue to run about in an awkward, half-conscious shuffle, presumably terrifying thenselves and any would-be aggressor. A state of self-acknowledgment of food chains and superior aggressors brings us onto Liston. An unpopular champion, Sunny Liston first fought Ali in defense of the World Heavy Weight title in 1964. At the start of the seventh round, rather than heading back into the ring, Liston surprisingly ducked under the ropes and headed off for the dressing room. The official story was that he retired with a hurt shoulder, but it was evident to all that he realized that he processed no answers to Ali’s speed and skill. Liston called-off a rematch in 1965 with only day’s notice, and the inevitable final meeting (2) lasted under two minutes with Liston spread-eagled on the canvas, a famously emotive image that recently caught Kaga’s attention. (3) At least Liston demonstrated that he knew himself and his limitations and used this understanding to protect himself from unnecessary harm.

Eight pages on from the introductory quote above, Ross inquires of Macduff; “How goes the World, Sir, Now?” Only those holidaying on Jupiter for the past couple of years would have not noticed that the world has become more like Macbeth’s hell, and to which, Kaga seems to advocate the highly potent coping methodology of myotonia congenita. It is as if the world’s current state, with the endless stream of bad and disaffecting news has triggered Kaga’s off button, a desire for occlusive oblivion. A vast multi-panel centrepiece painting of Hell (4), contains no one (good) awake: Kaga’s usual cast of characters, Usacchi, Kumacchi, Alex, Pandas, Panda-angels, Pretzel men, joined by a few new members, including a strange, stylized Japanese comic book elephant, all sleep in positions reminiscent of Liston’s KO. The abundance and pervasiveness of Kaga’s metaphor of self-induced, self-protective narcolepsy, tacitly underscores the inherently innocent construct of Kaga’s fantasy world. Following Macbeth’s logic of “the innocent sleep”, they must all only be visitors or accidental tourists to this realm of the damned.

Complex narratives, sub-texts and human dualities, typical of Kaga’s practice, start to emerge; individuality and social identification, innocence and experience, integrity and corruptibility, nature and nurture, freedom and constriction. Atop a sculpted mountain Usacchi, Kumacchi and Robert (central Kaga avatars) sleep soundly, seemingly safe in the knowledge that they are guarded by dozens of mustachioed Pretzel men. Seeking narrative keys from previous Kaga works, for example, his 2009 animation, Factory, introduces the Pretzel men to represent individuality in an ‘indentified’ (5) world, and now they protect the sleeping artist himself. Moreover, Kaga’s recent use of fabric collage adds another willingly perverse dynamic. He recounts that as a child his mother had a passion for fashioning quaint home-made quilted fabric bags for school, in which Kaga and siblings would carry, books, lunch and gym equipment. Kaga has taken this childhood memory of social embarrassment and negotiated it into his on-going discussions and contextualization of Otaku (6) culture in a harsh and unsympathetic world. As a self-professed ‘otaku’, Kaga’s work withdraws further into its imaginary world as a self-protection against the ‘real’, so his imagination becomes more real to fellow otakus. Kaga’s creation, the unrestrained libertine Usacchi is increasingly adopted as cultural hero, a figure-head, standing against personal injustice.

There are those that do not sleep in this new body of work, a chorus line of radiantly happy characters link hands across one of the panels of Hell. They wear retro silver space-suits, to protect them from the sleeping sickness that otherwise pervades the world. They are either evil and up to no good or have happily found a way to escape the ‘grey flats’# of this world to a better place. Better still, perhaps they are visiting aliens from another world who have come to fix things while we sleep. Please.

Atsushi Kaga studied Fine Art at the National College of Art & Design Dublin and is currently an artist in residence at the Irish Museum of Modern Art. Other recent residencies and shows include Galleria LEME, Sao Paolo, The Fountainhead, Miami and a related solo presentation with mother’s tankstation at NADA, (all 2009).