Introduction

Eddie Martinez makes graphic, still life and figurative paintings that combine and distill a knowing mixture of naïf cartoon imagery with the primitive rawness found in expressionism. Die Brücke, Art Brut, and a bit of Pop and Folk Art are fodder for his synthesis of wide associations.

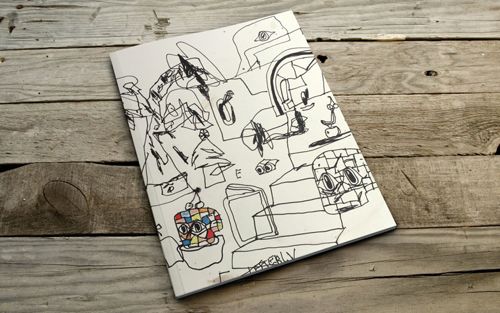

Distinctly idiosyncratic in appearance, his artworks have dense chromatic colors, off key striations, and rapid-fire brushstrokes that belie his run’n gun command of perspective, line and form. A prolific drawer, Martinez paintings have the episodic freshness of a sketch and the literate charm of a raconteur. His gift is to improvise and enable spontaneous thought and lucid intellect to reconcile improbable planar geometry. The result is a considered spacing and “unsymmetrical” balance that complements the slashing vertical and horizontal brushstrokes.

Paintings such as Backgammon Blues are less about the suggested subject matter than the relationship of color to ground and form to improvisation. The head is red/orange with a broad cerulean face and black oversized almond shaped eyes set atop an askew body on a dominant white ground. A green sweater vest with exposed flesh is all triangles with the arms and shoulders rounded off to the sides. With its geometry of blacks and beige, the game board at the bottom of the canvas anchors the picture. His specific placement of the dice and backgammon checkers offset the stolidity of the painting’s top half.

Formal strategies aside, Martinez’s works are quite often narrative-driven ironic depictions of the everyday: a slacker’s accumulation of stream of consciousness observations, notations, and reflections. It’s a repertory of recurring characters, portraiture, scenarios, and material objects that correlate to a madcap life and the artist’s humorous detachment from the multitudes. With its old fashioned early 1980s touch-tone phone, Warhol banana receiver (an iconic art historic reference found in many pictures) and titles that wittily play on opposites, Busy Signal or Serious Conversation epitomize the zany deadpan way Martinez tweaks mass iconography: in this case, a symbol of communication with the slapstick implication that we’re not always on the same wavelength.

Cherry picking his way through cultural symbols and metaphors, the gritty painter’s lingo of Eddie Martinez is perhaps a subconscious search for an epiphany. Color is an emotive construction, an off-key octave that embellishes the self-referential folklore of his central motifs. Like the Fauves, he gives order to pure painterly color with abstract flourishes. Like German Expressionists, he anchors himself in the rudimentary forms of the primitive and, in updating its tenets, seeks to make sense of an intangible 21st centurytopology.

The totemic blockhead figuration of Idaho outsider artist James Castle (1899-1977) come to mind in rough hewn works such as Intergalactic Gofish. A trio of personas sit at a table demarcated by thick black lines with an array of objects in front of them. A smudgy spray- painted undercoat seeps through the heavy black and white monochrome ground. The washy lightness of the torsos offset the weighty bulk of the heads, while a dense rectilinear composition evens out the middle perspective point by placing a blunt charcoal vase to the far left.

Graffiti, a trace of 1970s Sigmar Polke, and ’80s neo-expressionism subtly underscore thematic subjects such as Backstage Accommodations and Table, Quilt, Table #2. Identifying with items of utilitarian use and using repetition in a still-life format, Martinez schematically incorporates slightly modified sets of sequential icons within each painting. A tableau of arranged objects is displayed on tabletops that look like a billboards: an arcade of crudely rendered hats, fruits, boxing gloves, owls, snakes, shoes, polka-dotted mushrooms, diamond shapes, uncouth smiley faces, hat-wearing duck heads, vases, little potted plants, etc. These effects form a composite profile of an artistic scavenger’s personality and disposition towards material stuff. His own possessions and detritus have become mini-icons of individualism. As paint-bound talismans with a twist, they could be subconscious low-fi responses to image reproduction and media “virtualists”. This plastic analogy to animation characters includes early Cory Arcangel memes, Ben Jones pictographs, and the anti-aesthetic of Paper Rad. It could even two-dimensionally extend into the “Shape Projects” of Allan McCollum, which conceptually links social community, local tradition, and craft with the construction of iconographic symbols.

Indicative of the social agency Martinez stands for, friendship and community are clear leitmotifs. His figures wear “Picassoid” hats or bandanas to accentuate their outsider/band of brothers status, conspiring to make their way in this treacherous world.

Its Up to You and Me Brother #2 is an ongoing portrait series of two or more figures that most likely are depictions of Martinez’s extended artistic family. They are pals cut from a certain cloth, thick as thieves, with Darth Vader shaped heads. Out of numerous versions, one picture could be a take on the famous Shafrazi gallery poster invite of the collaboration between Warhol and Basquiat. Imagine their encounter when posing for the photo, Andy being the would-be bandit stealing riffs from the drug addled cerulean-faced Jean-Michel. It’s an odd couple straight out of daft Dubuffet crossed with late Philip Guston.

Guston had his repertoire of utilitarian things: he used books, light bulbs, and shoes as ammunition for social and political commentaries. Martinez is an incubator of ideas: constantly itemizing and cataloging possessions, he has his sporting themes, deck shoes, menagerie of animals, and simultaneity of place. Lost Luggage depicts protagonists donning boxing gloves, a good metaphor for the artist ducking it out in the studio and in life.

In the painter’s idiom, it’s the autobiographical symbolism that exerts a powerful impact on Martinez’s image production. His unorthodox style is more happy-go-lucky raw sentiment with a touch of Shakespearean absurdity than existential angst. Puck meets Donald Duck on the basketball court, discusses the world as a stage over a beer, and watches baseball on television afterwards.

Small works like Plantstracted and numerous (untitled) skull paintings are reduced to their most elemental surface shapes, combining the patina of cave paintings and a Neanderthal aesthetic. In this dense linguistic minimalism the faux naïf of ‘80s Donald Baechler or late ‘90s Tal R flat-lines into a brutalist frontal assault of paint; the innocence is demolished.

The classic still life, in its many historical guises, has occupied the mind of painters for generations. Ironically, this has an extrasensory resonance. Martinez has a knack for turning garish cliché and grotesque deformations into strong pictorial representations. His works are pleasurable pictures of insouciant decorative flair that riff on Matisse Oriental patterns with a showman’s love of color anarchy.

With a degree of devil-may-care abandon and controlled mark making, it is the performative actions that spontaneously produce Martinez’s peculiar yet compelling narratives. What he gets at is not so much about concrete reality but points towards an idiosyncratic memory of time and place, or as Freud might have put it, the psychology of his waking dreams.

Max Henry