Frauke Eigen’s new works lead photography into an area of the autonomous image usually assigned to painting. In her gallery and museum exhibitions over the past two years, the atmosphere and aesthetics of Japan have been the predominant subject of her black-and-white photographs. The works were oriented toward seismographically recording structural phenomena that step out of the usual field of vision as worthy of being captured in an image.

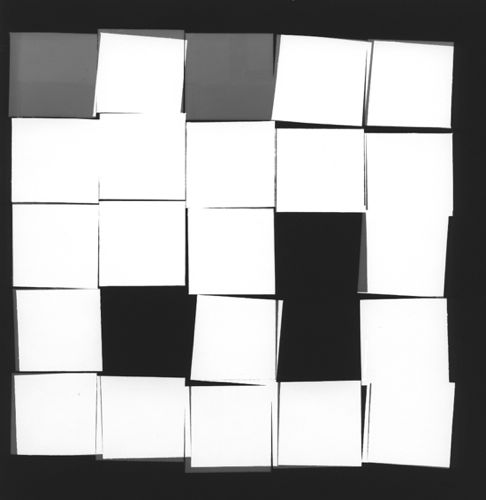

The most recent works pull the gaze back; the camera turns, so to speak, inward. No longer do outward happenings determine the reality of the image, but the artist herself provides the precondition for something to become an image. Images of beams, patterns, rays and patches emerge that only marginally admit a reference to the outside world. Rather, they create an independent combination of differences of line and surface which condense into a meaningful image.

The non-representational image has perhaps the strongest potential to orient itself toward the viewer in a way formulated by Georg Lukács in his aesthetics at the beginning of the twentieth century. In this aesthetic theory, works of art as a world of fulfilment are counterposed to people’s yearning for the reality of experience: what remains withheld from all other expressions of human living, or exists only in a very sparse and questionable way, is fulfilled in the art work. The schema of communication has, in the work, stripped off everything fragmentary – not only what is empty and abstract, but also the merely personal – and the absolute unity of the individual with the superindividual is said to radiate through their unification in the work, attained through a coincidentia oppositorum.